Preparing your project

Whilst incredibly rewarding, making stairs is challenging and mistakes invariably costly.

Before throwing yourself into StairDesigner to input your stair parameters and design preferences, and then output your manufacturing files, some ground work is vital.

Hopefully you have read our stair measuring tips for taking site dimensions and are now ready to start designing your stair.

The first stage is to compile a general overview of your project.

This should include:

- List of the wood sections that you’ll be using for each individual component: strings; handrails; risers; etc

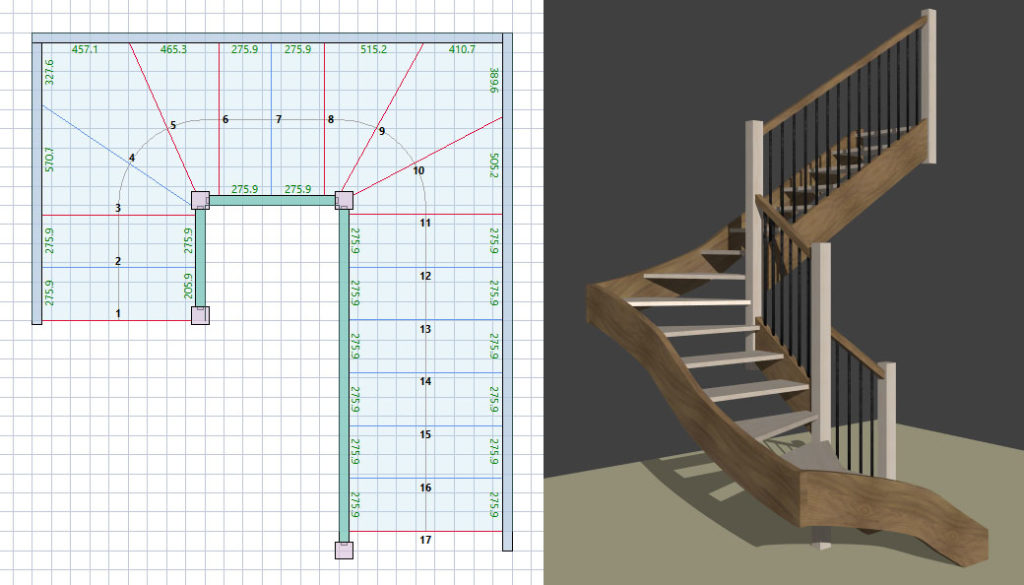

- Rough dimensioned sketch of the overall stair

- Dimensioned sketches of the assembly with the upper floor

- Dimensioned sketches of the assembly details of strings and handrails with newels and strings to strings

- Dimensioned sketches of the assembly of steps to risers

- Dimensioned sketches of the assembly of steps and risers to strings

Wood sections for stairs

If you are new to building stairs it’s a good idea to research what materials you will have available to build your project before starting the design.

The final sections of each of your stair components will depend on a number of parameters:

- The base material you want to use to build your stair: solid wood; laminated boards; manufactured sheet material; etc

- The dimensions provided by your local suppliers

- The aesthetics of your project

For general stair building here are our recommended minimum thicknesses for solid wood:

- Strings 35mm

- Newels 70mm

- Steps 30mm

- Risers 15mm

Hand or CAD sketching?

The best way to sketch out a project is to use a computer-aided design (CAD) programme. However, for most regular stairs you won’t need it, and will be able to input the project parameters directly into StairDesigner.

It’s only really necessary for complicated projects, where you’ll need to input precise reference points from your site measurements and from within the CAD package output the parameters you’ll need for StairDesigner.

A disadvantage of CAD is that you’ll have to know how to use it.

So if you’re not familiar with using CAD you’ll have to sit down and at least learn the basic functionality. If you make stairs regularly we would strongly suggest that you take the time to learn how to use a CAD system.

On the other hand if your project is fairly straightforward and you only design occasionally and you don’t know how to use CAD it’s perfectly feasible to set up your preliminary sketch with pen and paper.

As a suggestion, download nanoCAD, a good free CAD solution.

Draw a plan

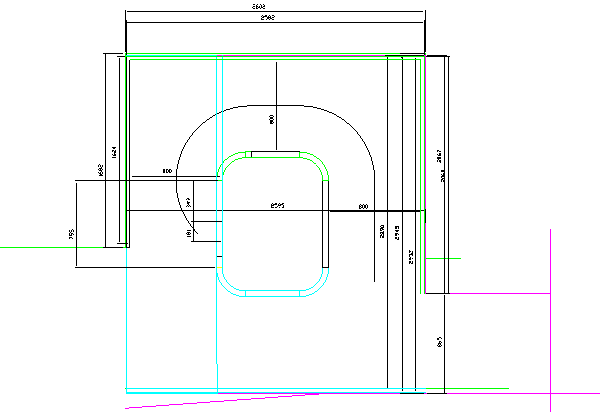

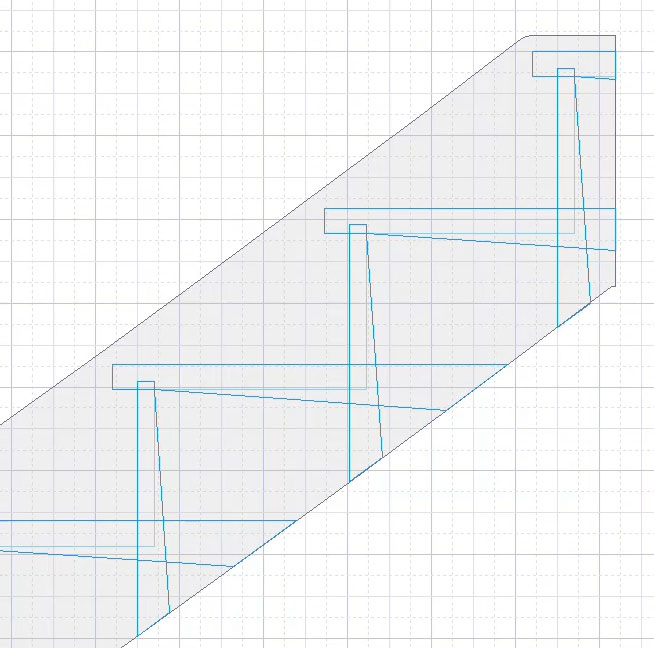

The first job is to draw a scale plan of the existing stairwell. If the project is simple a rough sketch with a few dimensions should be enough.

On the other hand if the stairwell is complicated you’ll have to draw a detailed plan and elevation views of the complete stairwell.

Once the plan of the stairwell is set out draw in where you would like the stair to start and finish.

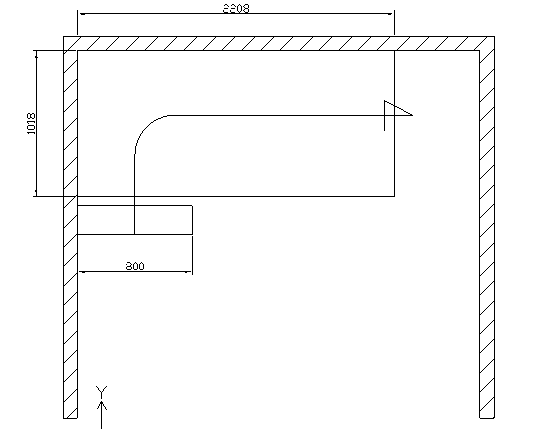

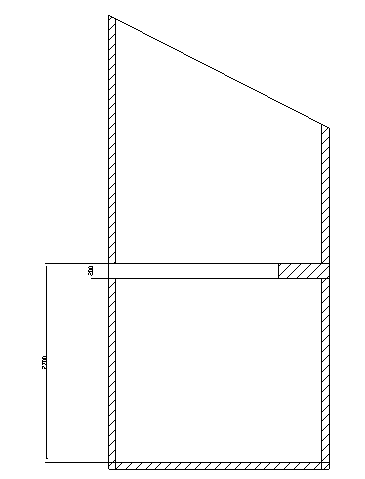

It’s also a good idea to draw an elevation view of the stairwell like this:

Here is an example of a more complex stairwell plan that rises up through 5 different levels:

Calculate headroom

The start of a stair can depend on the position of obstacles, doors, windows, other walls etc but more often than not, if the stair moves up inside a stairwell, it will depend on the minimum headroom that has to be allowed as a person climbs up or, even more importantly, goes down the stair.

The minimum headroom is usually 1m80. This can be very tight for a tall person going down and there remains a risk of them hitting their head if they are leaning forward. In most situations it’s a good idea to use 1m90 to 2m as a minimum and 1m80 only in extreme situations.

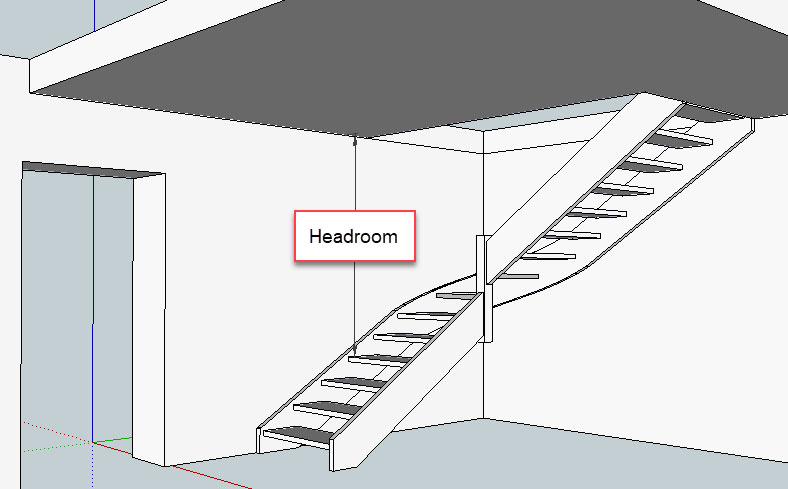

In the following illustration although the stair could start at the door the number of steps outside the stairwell will depend on the minimum headroom.

If making stairs manually it’s important to have an approximation of the position of the first step and it’s necessary to calculate the approximate start of the stair according to the headroom.

The minimum headroom is calculated by finding the maximum height of the step that’s just outside the stairwell. This is the key step we need to bear in mind.

Headroom step height

To calculate the maximum height of this step use this simple formula:

HS = TH – FT – 1m80

Where:

- HS is the headroom step height

- TH is the total stair height

- FT is the upper floor thickness

- 1m80 is the minimum headroom

Note that it’s often quicker on site to measure the distance from floor to ceiling than the thickness of the upper floor.

This under ceiling distance UC is of course equal to TH – FT.

To calculate the number of steps outside the stairwell we have to know the height of each step or rise. To do this, divide the total height TH by a number that gives a rise between 160mm and 210mm. The lower the rise the easier the stair will be to climb.

Then divide the height calculated for the headroom step HS by the rise and you have the number of steps outside the stairwell.

Step width calculation

The actual position of the first step will depend on the width of the steps.

To calculate the step width you can use the Blondel’s formula, also known as the Stair Rule:

2 x rise + width > 600mm < 640mm

This gives the minimum width of each step as 600 – (2 x rise).

Multiply the number of steps NS by the step width SW and you’ll have the approximate distance the first step will be from the edge of the stairwell.

This process is the standard way to calculate stair headroom and it’s important to understand how this is done.

Automatic calculation of headroom and the Stair Rule

As we will be using StairDesigner to design our stair, the programme proposes some neat tools that will help optimise all these parameters.

To gain time it’s possible to make a stair in StairDesigner with a default step height and width and to optimise from there.

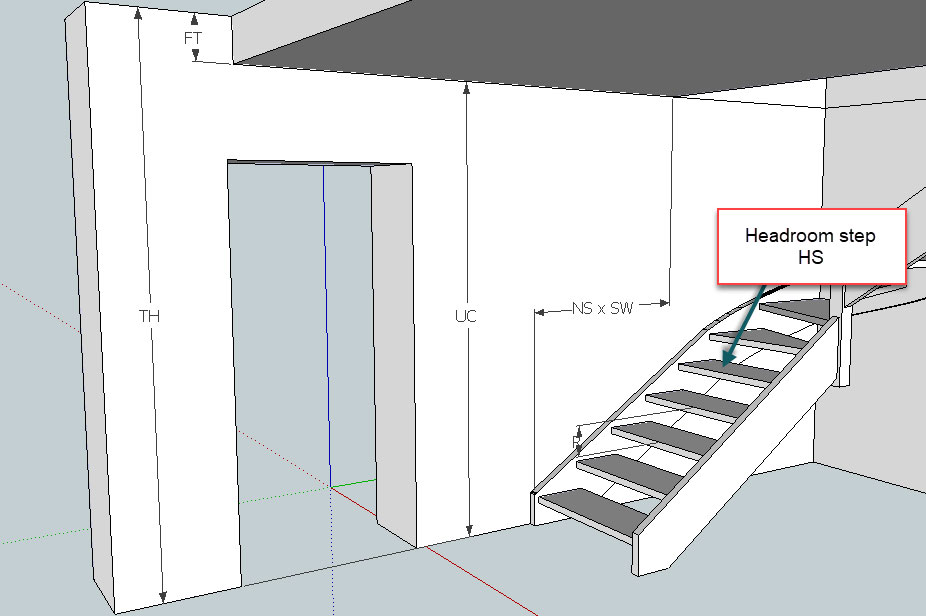

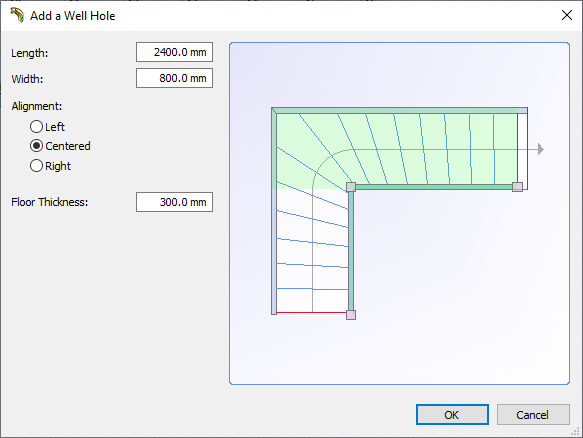

The headroom control allows you to define the stairwell dimensions and floor thickness:

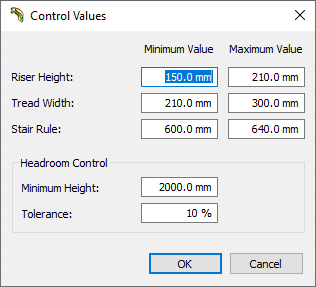

The control value for a minimum height can be set here:

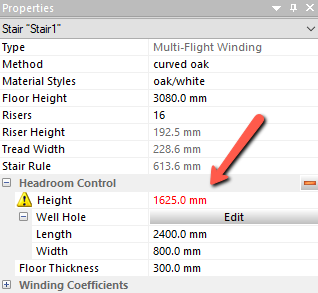

You’ll then see the actual headroom in the Properties menu. Adjusting the number of steps/risers and other parameters will immediately update the headroom value.

The Stair Rule value is also dynamically updated as you edit (control values are shown above for this too), so it’s very quick to adjust your stair to ensure it’s safe.

For more information go to these two pages in our Help Centre:

General stair parameters and optimisation

Draw sections at arrival

One of the points often ignored by amateur stair builders is the optimisation of the assembly details where the stair will meet the upper floor.

There is an infinite variety of possibilities and each stair will have it’s own problems and solutions according to the situation at hand.

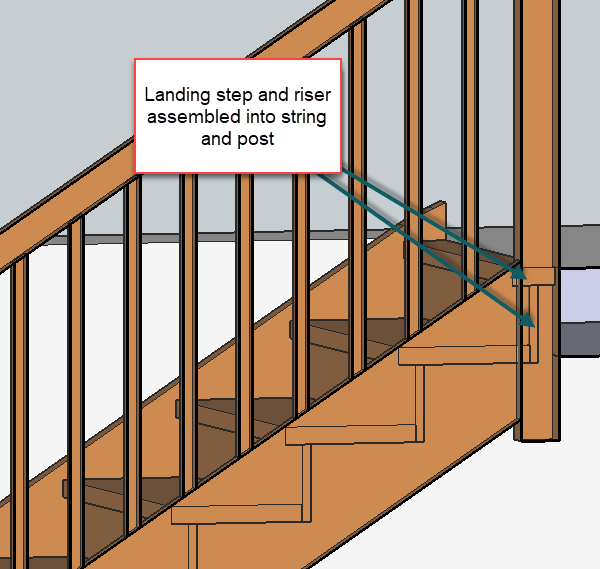

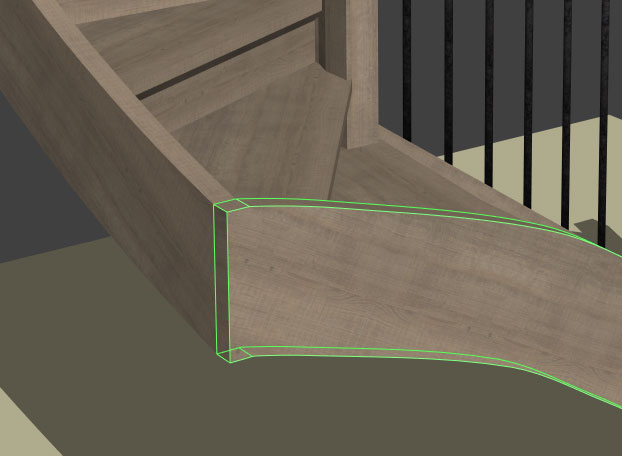

One point before we start is that whenever possible you should add a landing step to your stair.

The landing step creates a harmonious transition from the stair to the upper floor and finishes off the stair allowing the last riser to be assembled to the strings and newels of the stair.

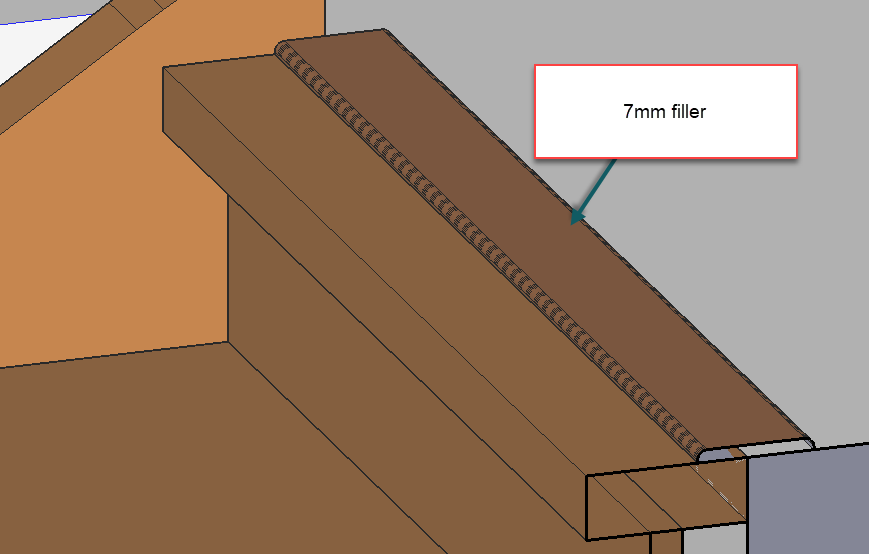

Note that it’s often difficult to get a perfect joint between the landing step and the upper floor so allow for some way to fill any gap.

You can use a strip of wood or a metallic filler but this isn’t a great solution aesthetically.

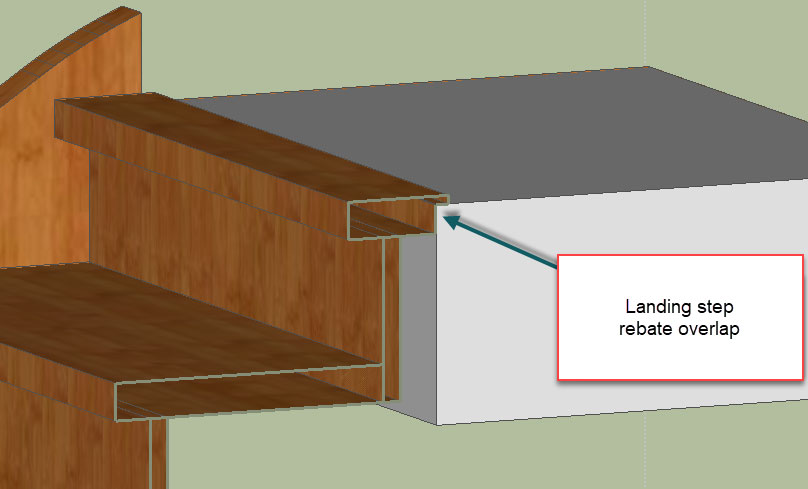

A more elegant way of covering any eventual space is to rebate the landing step.

In this case don’t forget to increase the total height of the stair and the length of the last flight according to the overlap of the last step onto the upper floor joist.

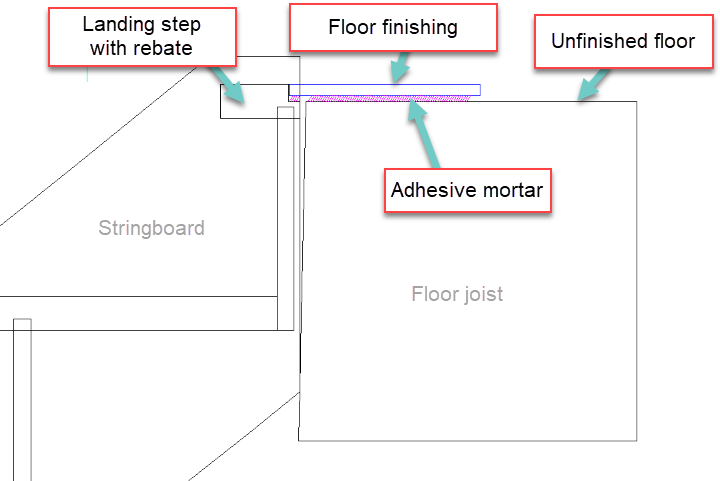

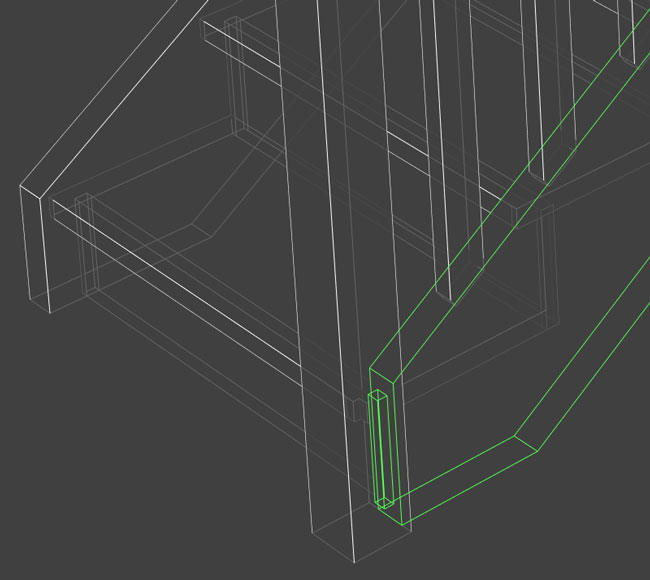

Here’s a final option which looks very neat.

Create a small cut out at the back of the last step and position it above the unfinished floor level, at a height sufficient to accommodate the floor finishing and any adhesive. The finishing sits across the joist and staircase and hides any gap perfectly. The gap itself may vary if the joist isn’t straight; this solution manages that variance too.

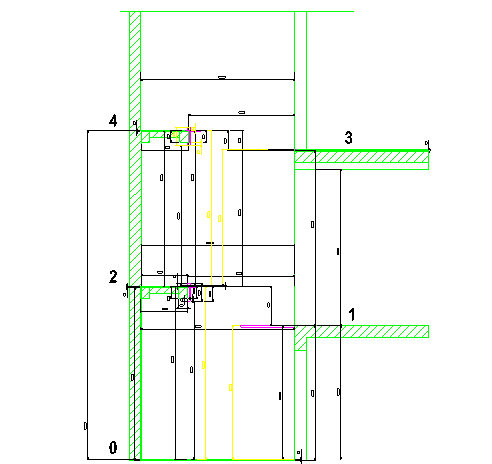

The CAD drawing below highlights this option:

Another key question that arises as a stair meets the upper floor is how it will assemble to other

components on the landing.

If the stair doesn’t assemble to other components and just has to rest against the upper floor joist the easiest solution is to rest the stair against the stairwell.

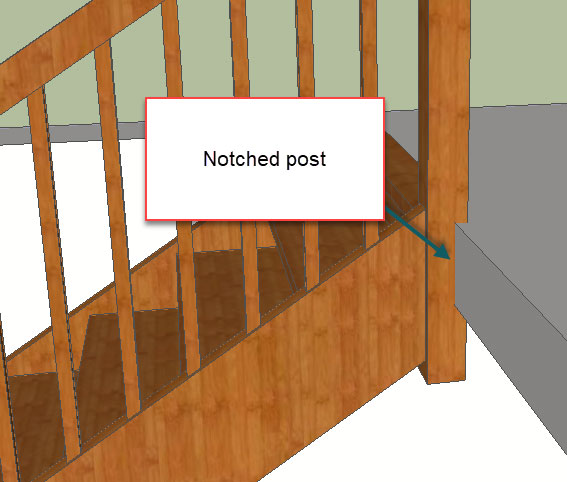

Cutting a notch in the last post will enable the stair to hook onto and rest on the floor.

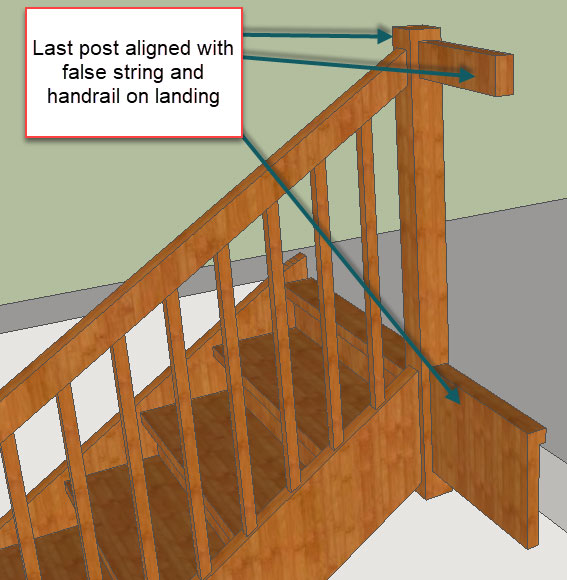

If the stair has to assemble to elements on the upper floor the position of the last posts and strings will depend on how you want to align the upper floor posts, strings and handrails.

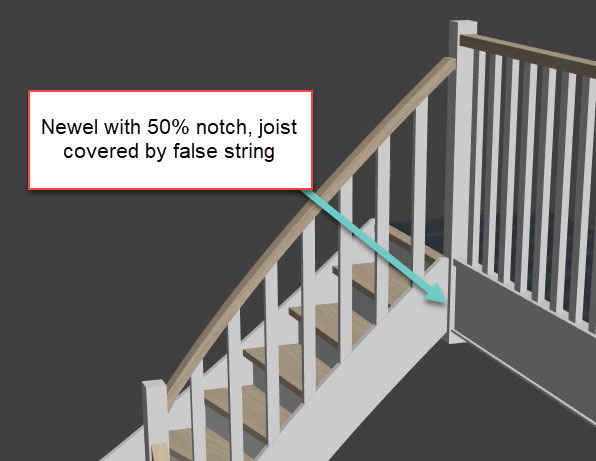

If there is a false string covering the face of the joist a simple notched newel may suffice.

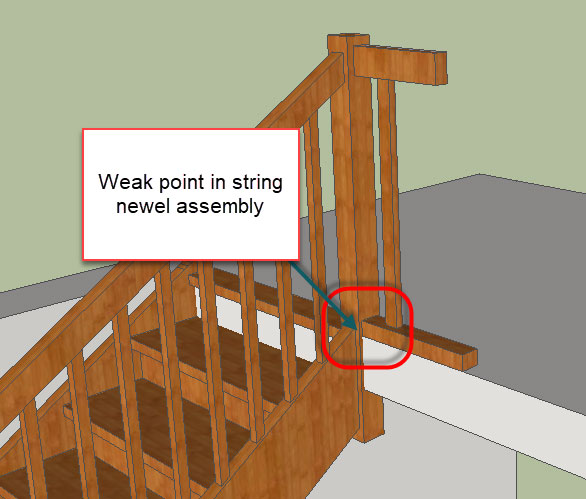

On the other hand if the upper floor balustrade is resting on the edge of the stairwell the deep

notching of the last post may weaken its assembly with the string.

This shouldn’t happen if you include an overhang of the balustrade beyond the stairwell edge. This is often advisable so you can add below this overhang a cover strip to hide the edge of the floor finishing.

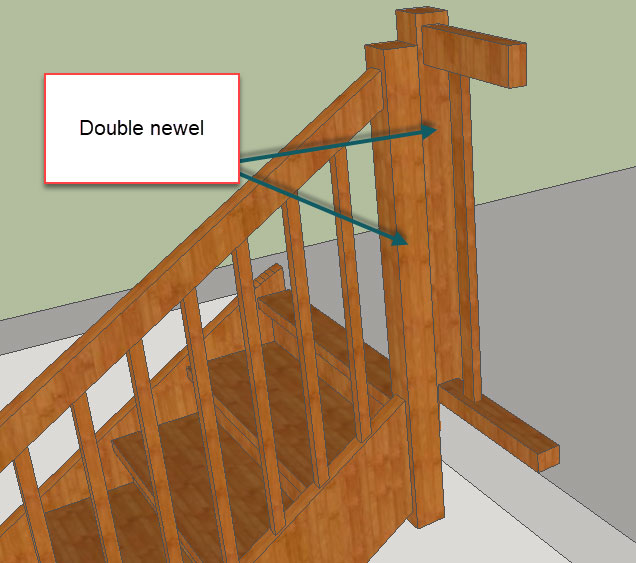

An alternative option is an arrival with double newels, it can be easier to make and give a stronger assembly. But it does look bulky.

Our preference is to use a single newel.

As a general rule set the notch at 50% of the width of the newel, which should be strong enough and ensures the balustrade over hangs the stairwell. Then if the edge of the joist is in good condition add a finishing rod below that overhang, otherwise completely hide with a cover panel / false string.

Here’s an example in StairDesigner with a false string:

Note that in each case the position of the newel and last step relative to the stairwell changes and will vary according to the solution you choose and the also the sections and positions of the newels, strings and handrails.

It’s important to draw how you are going to configure the way the stair assembles onto the upper floor joist to know what parameters you’ll use in StairDesigner.

How to assemble steps, risers and strings

When deciding how the different elements of a stair will join together it’s important to keep in mind how you will assemble and install the stair.

A stair that can be assembled outside the stairwell and hoisted or lowered into place can have assembly details that would not be possible to use if the stair has to be assembled in the stairwell.

This is true for the assembly details of the steps and risers as well as the steps and risers with the strings.

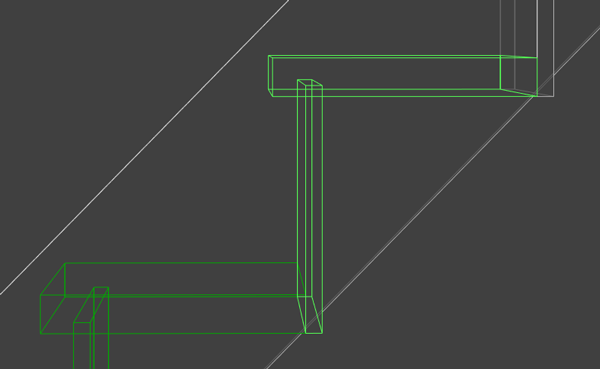

We have found that a reliable and straightforward step to riser assembly is for the riser to be grooved into the upper step, and sitting behind the lower step, as shown below in StairDesigner.

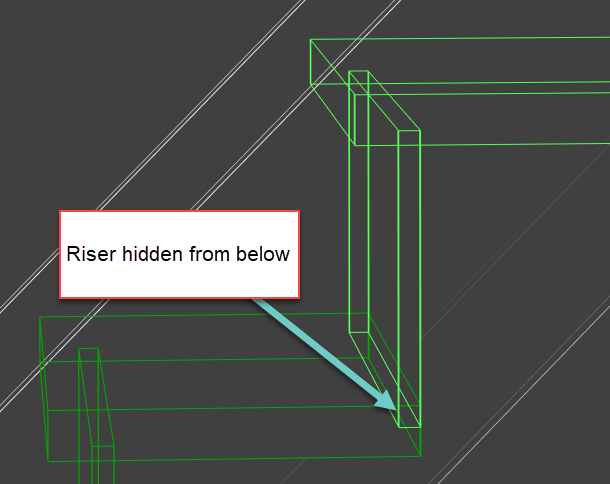

There are lots of other possibilities, for example if the staircase is visible from below. In this case it’s nice to hide the bottom of the riser as it meets the step, so just the step is visible from below.

In this case we set the riser priority to ‘no’ and the lower offset to 15mm.

How to assemble steps to strings

In much of Europe the traditional way of building stairs allows the stair to be assembled in the stairwell.

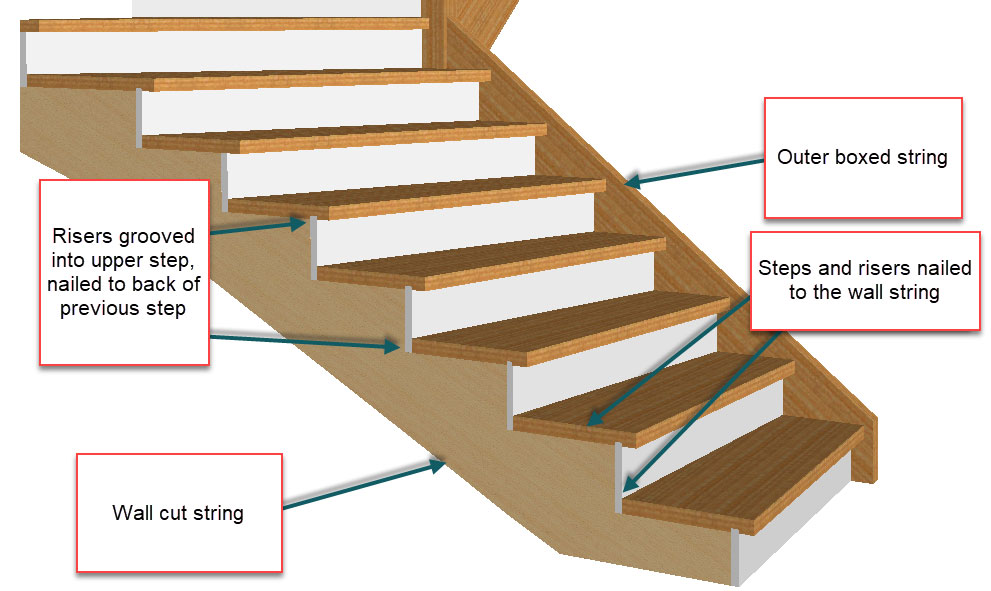

In general the outer string is a solid boxed string and the wall string a cut string. This diagram shows the traditional assembly of European style stairs.

Making stair stringers this way allows you to position the strings, place the risers and then place the steps without moving the strings, much easier and needing less space than having to assemble the complete the stair and then lower into the stairwell.

However this method has two disadvantages:

- If the steps shrink a gap will appear along the back edge where the step assembles with the next riser

- A plinth has to be cut to cover the gap between the steps and the wall; cutting the plinth to move around the steps and risers is a tedious and time consuming task

To get around these problems it’s possible to build the wall string in 3 different parts…

Boxed string in 3 parts

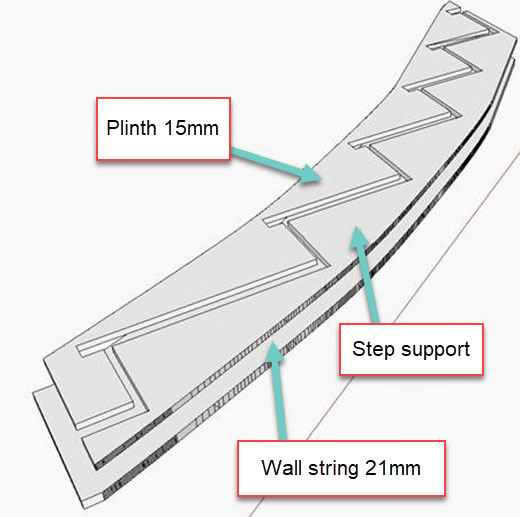

Let’s make a dismountable boxed string that’s say 36mm thick with 15mm housing.

Take a board that has the same thickness as the depth of the housings and screw it to another board of 21mm to have the total 36mm.

Make sure the screws are not where the housing will be routed out.

Mark up the board and rout out the housings with a hand router or CNC.

The housings will cut the 15mm boards in two.

Unscrew the 15mm board that is the lower part which we are going to call support and the upper part called the plinth.

Glue and screw the support back into place.

When installing, the steps and risers can be screwed on to the support and the plinth pinned on

after everything is in place.

If you keep the screw heads close to the end of the step, they will be hidden when you pin the plinth on to the string.

In this way the complicated plinth is automatically cut when you rout out the steps and risers.

Here’s a photo of a 3 part wall stringer being assembled in the workshop.

If the underside of the stair in not visible and/or the outer string is a cut string, it’s possible to assemble the step and risers easily.

In the case of a stair with boxed strings and a hidden underside the step and riser housings can be extended on the lower edge of the string and steps and risers pushed in from under the stair.

Housings can also be opened to allow wedging which makes assembling the stair in the stairwell much easier. Here is that set up in StairDesigner:

How to assemble strings and handrails to newels

The traditional way to assemble strings and handrails to newel posts is the mortise and tenon joint.

To pull the joint tightly together, tricky due to the angle of the strings and handrails, use a draw pin.

An alternative way to assemble both strings and handrails is to use a coach bolt and some sort of alignment system like dowels, false tenons, biscuits or dominos.

This enables you to simply cut strings and handrails on the joint line and the bolt has plenty of pulling power to pull the joint tight.

In general an 8mm x 120mm coach screw with dowels for handrails and false tenons or dowels for the strings works fine.

Here’s a photo of a handrail using dowels.

How to assemble strings to strings

When there is no newel post, strings must be assembled string to string.

This joint is also best screwed using 6 x 90mm screws.

You need to decide which string overpasses the other. Generally you don’t want to see the join, so make the visible string overpassing, in the quarter turn example below that’s the lower string.

Alternatively you can make your stair stringers with a mitre joint.

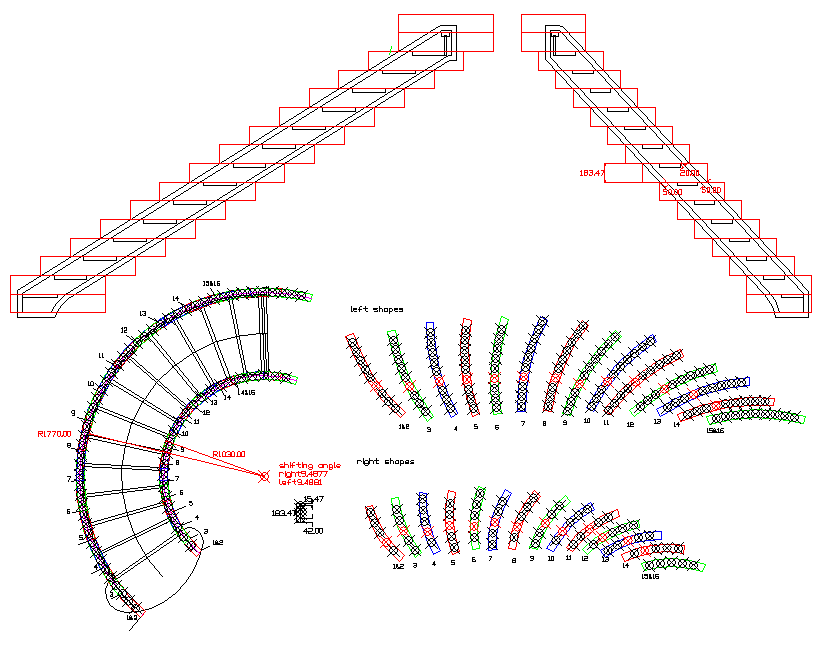

Curved parts: an overview

Curved stairs and building curved stair parts is a particularly complex subject within stair building.

Although StairDesigner will give general drawings and information to set up a curved stair the detailed manufacturing drawings will have to be drawn up from the StairDesigner plans.

Setting up these manufacturing drawings will require extensive editing of the StairDesigner DXF files or paper plans.

You might be interested in our proprietary horizontal laminates technique (example below) for making stair stringers, an excellent pro solution but a manageable project for an amateur woodworker too.

We can support you with curved stair manufacture on our forum, or you may be interested in our 1-2-1 StairPlan design service.

Conclusion

If you are a professional stair builder, please contact us for an online demonstration of the software. Here are more details on the design and manufacturing capabilities of StairDesigner.

If this guide has inspired the woodworker inside you, please consider completing your design with StairDesigner. We offer an alternative to buying the software that’s great if you’re working on a one-off project. This is called our StairFile service. It combines a cut list and plans processing service with advice on how to build stairs from our expert team.

Happy woodworking,

The Wood Designer Team